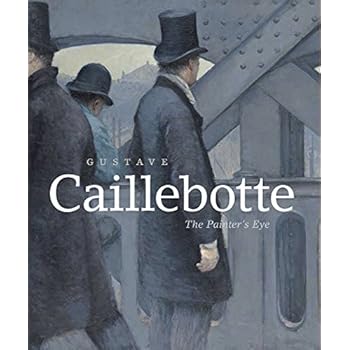

Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter's Eye

Category: Books,Arts & Photography,History & Criticism

Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter's Eye Details

Review “A well-upholstered fauteuil of a book that readers can settle into. . . . Caillebotte is fascinating precisely because his style seemed, to his contemporaries, to be not style at all. It was ‘photographic’—not a term of praise in the 1870s, but a fundamental one for art a century on.” (Bookforum)“Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye is the richly illustrated and impressively researched catalogue of an exhibition shown at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX. Curators Mary Morton and George Shackelford establish once and for all the pivotal significance of Caillebotte’s often overlooked or downplayed paintings. The exhibition focused on the work Caillebotte showed with the Impressionists, dating from 1875 to the early 1880s. The catalogue demonstrates that although he was a friend of all the Impressionists, Caillebotte was closest to Edgar Degas in style and focus. Essays by the curators and other art historians spell out the rich intellectual, literary, cultural, and artistic contexts in which Caillebotte oriented himself in late-19th-century France. Caillebotte, readers learn, was a keen observer of urban and suburban modernity. He rendered on canvas the psychological complexity of a French middle-class man’s experience of the new spaces and perspectives modern life afforded. Recommended.” (Choice) Read more About the Author Mary Morton is curator and head of the Department of French Paintings at the National Gallery of Art. George Shackelford is senior deputy director at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Read more

Reviews

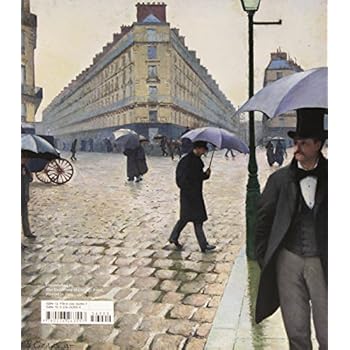

This volume is the catalogue to accompany the exhibition of the same name at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., from June to October 2015 and then at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, from November 2015 to February 2016. This is not the most comprehensive exhibition Caillebotte has had in the US (both the 1976 show organized by Kirk Varnedoe for Houston and Brooklyn and the 1994 retrospective in Paris, Chicago, and Los Angeles were larger), but in gathering fifty-seven canvases from the first half of the artist’s career, i.e., from around 1874 to the mid-1880’s, corresponding to the years of the Impressionist exhibitions, it has delineated more clearly than those previous shows what the curators call Caillebotte’s “Painter’s Eye,” i.e., the very individualistic and idiosyncratic vision that made his painting unlike that of any other artist of his generation and that created paintings of startling originality and striking modernity. John Rewald called Gustave Caillebotte a “timid” artist, and throughout all four editions of his groundbreaking and highly influential “History of Impressionism” steadfastly refused to see in him anything more than a kind of mini-Monet, a Sunday painter whose primary value to Impressionism was in paying Monet’s rent, buying up what Rewald considered otherwise “unsaleable” canvases of the “real” painters, helping to organize the exhibitions and generally bankrolling the movement. Given the information and the paintings that were available to Rewald by 1946, it is perhaps not hard to understand how he came to that opinion, for he seems to have seen mostly the landscape and nature studies from later in the artist’s life. But when one sees Caillebotte’s canvases of the Impressionist years, adjectives like “bold,” “daring,” and maybe even “fearless” suggest themselves; “timid” certainly does not come to mind. Neither, oddly, does “Impressionist,” and that may well have been Rewald’s sticking point, because only some of this work—and not the best at that—invites comparison with what we would generally consider an Impressionist style. Even though Renoir himself invited Caillebotte to join the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876, where he showed eight paintings, and though he continued to exhibit with the group, showing an additional fifty-nine paintings in four more exhibitions (missing only 1881 and the final one in 1886), and even though at times he was considered in the contemporary press to be the leader of the group, his paintings from these heyday years of Impressionism are visually distinct and quite divergent in theme, style, facture and just about every other way one can think of from “mainstream” Impressionism. Let’s give Rewald partial credit: maybe Caillebotte wasn’t a first-rate Impressionist painter after the scholar’s heart, but that doesn’t mean he was not a first-rate painter of another kind, and there was nothing “timid” about his art.The exhibition is curated and the catalogue edited by Mary Morton, head of the department of French painting at the National Gallery and George T. M. Shackelford, deputy director of the Kimbell. Their introduction points out some of the reasons why Caillebotte was so late to achieve the recognition that the other Impressionist painters enjoyed from the beginning. Chief among these is that since he did not need to earn money by selling his paintings, the vast majority of them were retained by the family after his death and still remain in private hands. (Even the Musée d’Orsay, which owns more of them than any other institution, has only four, compared to the dozens it has of each of his fellow Impressionists.) Combined with one part of the appended apparatus, an essay on his posthumous reputation from 1894 to 1994, there is some interesting observation on how an artistic reputation comes to be forged through strategic gallery sales, curatorial decisions, and other half-artistic/half-commercial factors. There are seven scholarly essays by academic and curatorial authorities, all clearly written and easily accessible. Some of the topics addressed are the artist’s “Deep Focus,” i.e., the extraordinary depth in some of his well-known paintings like “The Pont de l’Europe” (1876) and “Paris Street. Rainy Day” (1877), which the writer suggests is comparable to some early cinematic techniques; the surprisingly favorable way in which Caillebotte was viewed by much of the contemporary criticism, especially in comparison to the other painters; his interest in the furnishings of the bourgeois Parisian apartment as an indicator of social and interpersonal dysfunction; his rootedness in the realist tradition as transmitted to him through his teacher, Léon Bonnat (this is actually a short essay on Bonnat by the Orsay’s curator Stéphane Guégan); and the relationship of his paintings to contemporary photographic practice and techniques. In “Man in the Middle,” Dr. Shackelford himself makes a compelling argument that Caillebotte is best understood as occupying a middle ground between the two factions of Impressionism, i.e., between the painters of urban themes and modern life (like Degas) and the artists of atmosphere, landscape and light (Monet), and that his artistic evolution was from the former to the latter—unfortunately, as the writer concedes that Caillebotte was not a particularly inspired landscape painter and that in the second half of his short career, i.e., from the mid-1880’s to his early death in 1894, he made some fine paintings but “many more that are frankly rather ordinary” (16).The book itself is handsomely designed with an uncluttered layout and easily legible print, and it is profusely illustrated. The fifty-seven exhibition items are all reproduced full-page in the catalogue section, which is divided into several thematic areas (“View from the Window,” “Urban Interior,” “Observing the Nude,” etc.), each of which is introduced by a few pages of focussed discussion. The paintings are not individually commented on, but they all receive mention of some sort in the essays, which themselves have copious supportive illustrations including more of the artist’s paintings and some beautifully evocative photographs, some of these also printed full-page. The jacket text says there are 177 illustrations in all. One distinctive feature is the great number of detail studies, including over twenty-five full-bled pages, although I must say that it was not always clear to me why a particular detail was chosen for enlargement. Additional apparatus consists of a nicely illustrated “biographical chronology,” a good selected bibliography, an exhibition checklist with the requisite curatorial data, and an index of names and titles. There have not been very many Caillebotte exhibitions, which may be just as well; in their Introduction, the curators concede that out of a known oeuvre of around 500 paintings “only a fraction warrant the attention of a major exhibition” (16). But like the little girl with the little curl, when he was good, he was very, very good, and he is certainly very good in this exhibition and catalogue of his earlier work. Very warmly recommended to those interested in this period of French painting.